The Arms Race – The Fight Against Pathogens | Science Explained

“With all plant diseases, we are in an arms race. Don’t bet against the pathogen – the pathogen will always find a new trick. There’s no silver bullet”

– Professor Sophien Kamoun FRS

For farmers and researchers, crop diseases are a relentless, evolving threat. From wheat rusts to cassava viruses, pathogens are fast-moving, adaptable, and deadly. They’re invisible enemies with enormous consequences. This invisible arms race between plants and their diseases is one of the defining biological challenges of agricultural science today.

The Pathogen Playbook Is Changing

Historically, plant breeders relied on naturally resistant varieties to keep ahead of diseases, identifying a resistant strain and crossing them into local crops. But many of the most damaging plant diseases are also the fastest to adapt. Take wheat stem rust, for example: once thought to be under control, a virulent new strain called Ug99 emerged in the late 1990s, bypassing the resistance genes used in much of the world’s wheat. Ug99 posed a severe threat to wheat production worldwide.

While resistant wheat varieties have since been developed and deployed in some regions, the Ug99 lineage continues to evolve as a relentless agricultural enemy. Therefore, the fight against Ug99 is still ongoing – and this isn’t an isolated case. Rice blast, cassava mosaic virus, and banana wilt have all shown how quickly pathogens can evolve and just how vulnerable to outbreaks global food supplies can be.

Plants Have Immune Systems Too

Just like humans, plants have built-in immune systems; complex, layered defences that help them detect and respond to infection. But unlike us, they don’t have white blood cells or antibodies to help fight off these illnesses.

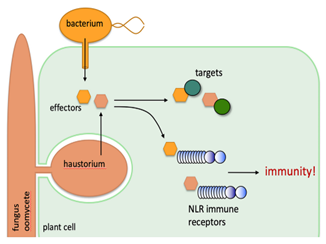

Kamoun explains: “These pathogens are incredibly good at hijacking plants. They do it by secreting molecules—proteins we call effectors—directly into plant cells.”

Think of a venomous snake. The venom paralyses the prey by targeting its biology. Pathogens do the same: their effectors act like biochemical venom, sabotaging the plant’s internal processes to create a better environment for the microbe to thrive.

The gene that encodes this effector lives inside the microbe, but the protein does its dirty work inside the plant. This is what evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins famously called an extended phenotype—a gene expressed in the world outside the organism (4). Just as a spider’s web is shaped by its genes, so too are the hijacked cells of a plant shaped by pathogen effectors.

How do pathogens infect plants? They secrete effectors to modify host plants.

But most plants aren’t helpless. They have immune systems, just like animals. And they’ve evolved to fight back.

Here’s how it works: if an effector slips into the plant cell, it might trigger a receptor—an immune sensor that spots something fishy. “It’s like a metal detector at an airport,” Kamoun says. “Try to sneak a weapon through, and the alarm goes off.”(5)

These immune receptors come in two main types:

-

- Pattern Recognition Receptors on the cell surface, which detect general pathogen signals.

- NLRs (nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat receptors) inside the cell, which detect effectors directly.

But pathogens evolve fast. Over millions of years, they’ve learned how to avoid detection—and worse, how to disable the immune system altogether by evolving new effectors to suppress plant defences. Some like rice blast can produce hundreds of effectors, flooding the plant with misinformation.

Plants counter by evolving new NLRs that recognise the newest effectors. It’s an evolutionary back-and-forth: a molecular arms race.

For over a century, plant breeders have used R genes—genes that code for immune receptors—to build disease resistance into crops. But the story repeats itself.

“We breed a new variety of wheat. It’s highly resistant. And then—boom—two years later, it’s completely blown away,” Kamoun says. The problem? That resistance usually hinges on a single receptor. All it takes is one mutation in the pathogen population to bypass it. A single spore in a field full of millions.

This is the cycle of boom and bust. And it has defined the history of plant breeding.

Gene Stacking – Betting Against the Pathogen

“There is no silver bullet,” says Professor Jonathan Jones FRS of The Sainsbury Laboratory (TSL), echoing a hard-earned truth in plant pathology. But unlike many, Jones has proposed a strategic solution to the boom-and-bust cycle in crop breeding—gene stacking.(6)

“In the same way that hepatitis B and HIV are treated with combinations of drugs, we can slow pathogen evolution by combining multiple resistance genes,” he explains.(4)

Jones’ idea is simple but powerful: stacking several immune receptors together in a single plant genotype dramatically raises the bar for pathogens trying to break through. “If you bring in five genes to fight rust disease,” he says, “the odds become really tough on the pathogen.”

His team has pioneered methods to rapidly identify and clone R genes from wild relatives of key crops like potatoes and wheat. These genes work synergistically, offering durable, layered defence.

But even with a strong genetic defence, the pathogen is always adapting. “We have to keep an eye on what the pathogen is doing and respond with updated breeding,” Jones warns.

Gene stacking represents a major step forward in durable resistance breeding—a vital tool to improve food security for millions of farmers.

It’s Not Just About Yield

When plant diseases reduce yield, the knock-on effect has dire consequences for food security, livelihoods, and local ecosystems. In regions where farmers can’t afford pesticides or crop insurance, a single outbreak could mean complete financial collapse. In Southeast Asia, banana wilt has spread rapidly due to monoculture plantations, leaving communities without a replacement cash crop. And in Nigeria, cowpea farmers have faced repeated infestations of Maruca pod borer, for which affordable and accessible resistance options have been limited.

The fight against pathogens also raises ethical questions. Who has access to the resistant genes? Are smallholder farmers benefiting from the new technologies being developed? And how do we ensure that today’s resistant varieties don’t become tomorrow’s vulnerabilities?

One recent example comes from northwest China, where potato growers are now adopting improved methods to monitor and prevent late blight — a disease infamous for its role in the Irish Potato Famine and still a major threat today. Working with scientists from the International Potato Center (CIP), farmers are combining traditional knowledge with cutting-edge disease forecasting tools and resistant varieties. It’s a small but powerful demonstration of what’s possible when science meets boots-on-the-ground farming.

🔗 Read more about the project in China

(Image courtesy of International Potato Center)